The Curious Case Of Constable W. H. Willshire

William Willshire was one particularly bad egg.

Central Australia in the 1880s was considered the outer frontier.

In some ways it still is, and continues to be most people’s image of what epitomises the Australian outback.

When William Willshire went to serve as a police officer there, the town of Alice Springs didn’t exist. There were no large settlements, only cattle farms and isolated outposts.

They were connected by the thin line of the then recently built Overland Telegraph.

The first European land owners tried to establish a good relationship with Aboriginal people. Many let the traditional caretakers continue to use their country as they always had.

They established some form of truce.

However, as the number of new settlers increased, these relationships progressively soured.

The growth of the cattle population encroached on traditional tribal lands and became competition for natural resources.

Along with this, missionaries established outposts and tried to convert the ungodly ’natives’ to Christendom. This brought about many conflicts.

The government was persuaded by pastoralists to set up a police force to maintain peace between all parties.

Aboriginal people were officially considered members of the British Empire, and thus, were citizens with the same rights as other members of the realm.

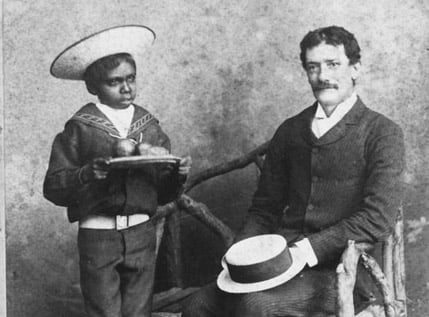

William Willshire was fresh to the force when he was transferred to Heavitree Gap, a natural break in the MacDonnell mountain range where later the town of Alice Springs was established.

In the beginning Willshire shared his duties with an Austrian count, Erwein Wurmbrand, who was notorious for his brutality.

Undoubtably, Wurmbrand educated Willshire in how to deal with the ‘native’ situation. Eventually, Wurmbrand was transferred to another district and Willshire was left to his own devices.

This in itself seems strange, a single officer responsible for keeping the peace in an area of hundreds of kilometres.

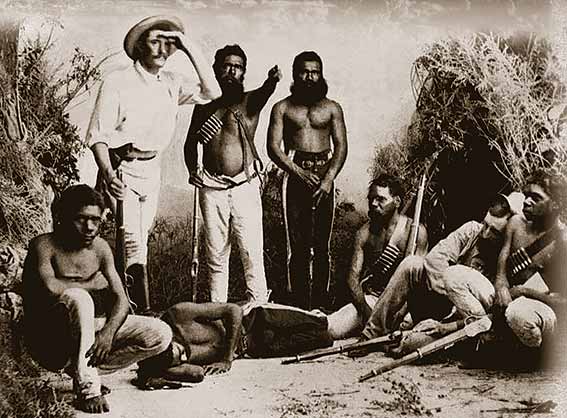

The gun was the principle enforcer of the law.

Willshire’s posse consisted of Aboriginal men enlisted for their knowledge of the land and language. They were underpaid and it is questionable why they joined the force in the first place.

The incentive was probably that Native Police had more rights than their relatives. From what I have read, it appears they laboured under the same conditions as their non-enlisted tribesmen.

Willshire’s primary weapon was fear.

He adopted a stance that the Aboriginal population needed to be subdued.

He achieved this through violence and outright murder. For this he had the wholehearted support of the farming population although it did bring him in conflict with the missionaries.

The Indigenous population were caught in the middle and, under his watch, any rights they had steadily eroded.

Most of what Willshire did is not officially documented. Even though it was his job to file reports on his activities, this only occurred on rare occasions.

Curiously, he was not a stranger to the written word. Somehow he managed to publish three books about his experiences. From the little I have read, it is clear he was quite an eloquent writer and had an intimate knowledge of Aboriginal culture.

His dubious opinions of Aboriginal people are also clearly stated and his methods as well.

It’s no use mincing matters, the Martini-Henry carbines at the critical moment were talking English in the silent majesty of these eternal rocks.

Towards the end of his time in the Centre, which lasted for 9 years, he had free rein and could tell his superiors whatever he wished.

Thankfully, this was all brought to a halt.

The amateur ethnologist and sub-protector for the Aboriginals in the area, F. J. Gillen, investigated one particularly brutal incident and had him brought to trial.

The trial only lasted fifteen minutes and Willshire was acquitted of all charges.

Most of the evidence was based on interviews with Aboriginal witnesses. Much of it was contradictory and Willshire walked free. Beyond this, the government couldn’t be seen to allowing his kind of conduct.

To condemn Willshire would had meant the government would also have had to take responsibility for his actions.

After his methods came to light he was transferred several times and eventually he became a nightwatchman at the Gawler Road abattoir in Adelaide.

Willshire was not the only person who carried out a consistent reign of terror on Indigenous people.

In some ways, although he was no saint, he shouldered the blame for a great many other lawmen, missionaries and pastoralists who inflicted pain and suffering in outback Australia.

He was only the tip of the iceberg.

Although his aggression was tempered this type of thing continued on for many years, even as late as the 1930s.

Do you like to read?

Sometimes it’s impossible to get home.

Combining magic, mysticism, wisdom and wonder into an inspiring tale of self-discovery, Loreless is an adventure story which will keep you guessing.

Hit the big red button and go check out the book.

In Loreless I wrote a flashback in which one of the protagonists ancestors suffers Willshire’s form of treatment.

I used not only Willshire’s story, as a central part of the research for that chapter, but other instances of frontier violence.

I found it a particularly difficult subject to write about. However, I felt it was necessary to give as complete a picture as possible about the Aboriginal experience.

The novel is predominately about coming to terms with what has happened in the past, and in some way trying to work out where we went wrong.

It is also about trying to find balance in a multicultural society.

Coming to terms with all these things is still a worldwide problem.

If we can’t face up to the failures of our ancestors, how can we possibly go forward and make things right in the future.

Is there a difficult subject you're trying to come to terms with?

Leave a comment below or join the mailing list and let me know.